Tor.com comics blogger Tim Callahan has dedicated the next twelve months to a reread of all of the major Alan Moore comics (and plenty of minor ones as well). Each week he will provide commentary on what he’s been reading. Welcome to the 20th installment.

The overarching structure of Watchmen starts to fall apart in the second half of the series. Or, perhaps it’s fairer to say that the schema changes as we enter more deeply into Act II. The odd-numbered plot-heavy issues and the even-numbered character background issues don’t quite continue into this second half of the series. The pattern becomes a bit more fragmented, and we spend less time on plot mechanics and more time with the underlying emotions of the characters themselves.

Maybe it’s better to say that the crystalline structure of the series becomes more organic as it develops, as the characters come to life on the page as more than just analogues for mostly-forgotten heroes of the past.

Yet, it’s second half also betrays it for what it is: Watchmen, for all of its innovation and influence, is still a superhero comic book story, an off-shoot of the classic sci-fi genre. Some would argue that its genre trappings make it less than a masterpiece. And while I don’t want to simply avoid the debate by saying that its imperfections are precisely what make it so interesting, what supposed “masterpieces” lack imperfections? Watchmen has its flaws, and some of them will get the spotlight in the issues I’ll talk about this week, but I find its retreat into traditions of superhero fiction and sci-fi storytelling to be particularly apt.

Watchmen provides a different perspective on superhero comics, but it’s never not a superhero comic. It doesn’t ignore what it is, but neither does it celebrate it in the way of the bombastic superhero comics of the past. Instead, it simply tells a story with an unusual level of intelligence and craft. And it raises as many questions as it answers, which is ultimately the legacy of any masterpiece.

If you’re not still thinking about a book long after you’ve read it, how good could it have been?

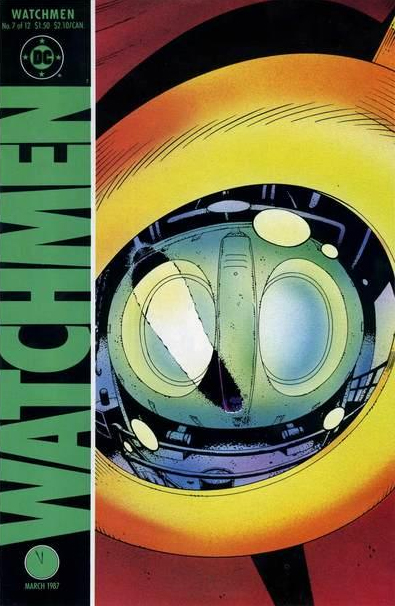

Watchmen #7 (DC Comics, March 1987)

Dan Dreiberg never gets a flashback origin story.

Out of all the major characters in Watchmen, he’s the only one who doesn’t get a spotlight issue from Alan Moore and Dave Gibbons where the story of his past is told. We get bits of his background through some conversations and some flashbacks involving other characters. We know, basically, that he’s kind of a nerdy guy who likes birds (owls, specifically) and gadgets and idolized the previous generation of superheroes. He would have teamed up with Captain Metropolis and the Crimebusters in a second, if that plan hadn’t gone up in flames thanks to Eddie Blake.

He’s a fanboy superhero, one who only gave up the costume because he wanted to follow the law, and when superheroes and secret identities were banned, he hung up his Owl Man costume, retreating into near solitude with only his regular visits with Hollis Mason and his dusty old Owlcave to keep him company.

I don’t know why Nite Owl never gets his spotlight in a flashback issue, but I suppose it’s because he doesn’t need one. There are no hidden depths to his character. No particular mystery. He enjoys playing the role of a superhero, and all that entails the costumes, the thrills, the saving lives, the punching out bad guys. He has no great depths to plumb, other than the surface-level psychology of his affinity for tight costumes and physicality.

And yet, if Rorschach is the beating heart of Watchmen, as I claimed last week, then Dan Dreiberg is its soul. For the first half of the series, he’s practically wallpaper. He’s there, he interacts with characters who come his way, but he’s mostly a passive participant, a straight man to their wackiness. He and Laurie fight some street thugs, but only in self-defense. But we get a sense, from his interactions, that unlike almost everyone else in the series, Dan Dreiberg is genuinely nice. In the world of Watchmen, that makes him seem soft, even weak.

But as this issue and the next begin to demonstrate, he’s not. He’s a superhero. He’s just been waiting for an excuse to put the tights back on.

In Watchmen #7, he does it for that most human of reasons: to impress a girl.

This is the issue where Dan Dreiberg and Laurie Juspeczyk, the Nite Owl and the Silk Spectre, both second-generation heroes, sleep together. Twice. And the fetishization of the superhero costume and equipment certainly plays a major part.

There’s a panel, though, on page 21, bottom of the page, where we first see Nite Owl in costume, and he looks more confident and heroic than he’s ever looked before. “Let’s go,” he says, flexing his gloved hand into a fist, ready for action.

And, yes, it may be sexual action that’s he’s talking about that’s certainly the end result of his escapades here but it doesn’t seem to be what’s on his mind. He’s back in costume, back where he feels comfortable, not because he’s a delusional maniac like Rorschach with no sense of identity beyond the mask, but because he gets to take his Owlship for a spin and “blow away the cobwebs.” He’s coming back to life, thanks to what’s happened to Rorschach, thanks to Laurie’s affections.

There may be selfishness and pride underlying what he does here (what they both do), but by the time Nite Owl and the Silk Spectre take flight over the city, and rescue civilians from a burning building, they do what’s right. They help people, even though they risk their lives to do so.

For all the deconstruction of the superhero in this series, this issue presents another perspective, humanizing larger-than-life costumed vigilantes not through extreme dysfunction, but through basic biological and emotional needs.

They need companionship and love and sex, but they also do what they can to save the lives of people they don’t even know. What’s revolutionary in Alan Moore and Dave Gibbons’s portrayal is that the first part of that last sentence is approached in an unflinching way.

Watchmen #8 (DC Comics, April 1987)

The previous issue ended with a declaration from Nite Owl, flush with victory after saving lives and sleeping with Silk Spectre: “I think we should spring Rorschach.” And here, they do. Though it’s debatable whether or not Rorschach needed the help.

This issue also gives Moore and Gibbons a chance to further layer in the various plot threads and echoes that carry through the entire series, while the previous issue kept the camera on Dan and Laurie throughout. In issue #8, though, we flash between Halloween on the streets outside Hollis Mason’s house to the newsstand to the pirate comic book tragedy to Rorschach in prison to a warning from Detective Fine to a mysterious island where the missing artists and writers seem to think they’re working on a secret movie project. And more.

It’s the issue with the most different things going on, and Moore and Gibbons deftly cut between the scenes and settings cinematically, without lingering on clever transitions as they used before. No this is where Watchmen starts feeling more like a traditional superhero comic, just moreso, with more plot, more extreme characterizations, and plenty of the kind of recurring background symbolism that makes the texture of Watchmen feel so complete.

Most of all, though, it’s the prison break issue, where Rorschach fights back against the mob boss and the thugs that would get their revenge against him, Dan and Laurie swoop in to try to bust him out during a riot, and Hollis Mason faces his final fate, a random victim of the violence plaguing society (he’s actually killed because the street gang confuses him with the Nite Owl who was involved with violence at the prison riots, so Dreiberg is directly to blame for his mentor’s death, though he never realizes his role in the whole thing).

Before the prison break scene, Dan Dreiberg basically lays out the whole conspiracy to Laurie. He proves himself to be more than competent at making sense out of the puzzle he’s been presented. And he says he needs Rorschach’s information to pull it all together. And maybe he thinks he does, but Rorschach doesn’t know anything Dreiberg doesn’t know. It’s just as likely that Nite Owl wants to rescue his old partner because of their shared history. Superhero camaraderie, something Laurie doesn’t really understand, having been forced into the role by her superhero stage mom.

So Rorschach is rescued in the most memorable action sequence in the entire series, though Nite Owl and Silk Spectre are practically incidental players by the time they arrive and Dr. Manhattan pops up to whisk Laurie away. The story closes on the young trick-or-treaters coming upon Hollis Mason’s corpse. The bloody murder weapon a statuette of Mason in his superhero garb lying amidst the wreckage of the apartment.

Things fall apart. Innocence is lost, yet again. If it had still lingered.

Watchmen#9 (DC Comics, May 1987)

The cover of this issue features a bottle of Nostaglia cologne, part of the Adrian Veidt (aka Ozymandias) line of fragrances.

The symbolism of the fragrance is clear and Nostalgia posters and ads appear throughout the series with Veidt leveraging the power of the past for his own personal gain, but it’s also about the characters in Watchmen failing to move beyond their own pasts. They are constantly bound up in who they were twenty (or forty) years earlier, in their superhero primes. There’s also the fact that the entire superhero genre feeds off nostalgia. That’s kind of an important point in the grand scheme of things.

But for plot purposes, the bottle of Nostalgia floating against a field of stars is a symbol of Laurie’s memories. Of her realization that her past was not entirely what she thought it was, and her epiphany on Dr. Manhattan’s crystalline palace on Mars that Eddie Blake was her biological father.

Her moment of clarity comes not through any one moment or memory, but from the cumulative effect of her fragments of memory, and the growing picture of Eddie Blake’s role in her life. She throws the Nostalgia bottle through the air, crashing into the walls of the crystal palace, but in the world of Watchmen, particularly when Dr. Manhattan is around, time doesn’t move chronologically. The Nostaligia bottle floats throughout the issue, appearing like a momentary flash-forward whenever it arrives in a panel, turning against its starry background.

The attention to detail in this issue is unbelievable, particularly when you realize as he illustrates in Watching the Watchmen that Dave Gibbons charted out the proper rotation of a partially-full cologne bottle against a constant field of stars. His diagram is in that book, and he used it to make the flight of the Nostalgia bottle completely accurate to the laws of physics and perspective. There was no need to do that. Even with the obsessive Watchmen fandom that followed, no one would have bothered to check the accuracy of a cologne bottle rotating through the air.

But Gibbons charted it out anyway, and that’s the kind of detail underlying the pages of this series. The mise-en-scene is rich.

This is Laurie’s character spotlight issue, as we see her childhood and the pivotal superhero moments of her past, as the embodiment of her own mother’s wishes.

And it’s the issue, set almost entirely on Mars, where Laurie convinces Dr. Manhattan that Earth is worth saving. That humanity is worth his intervention. But she doesn’t convince him through any rational argument. To Dr. Manhattan, the lifeless surface of Mars is as important as all the human lives on Earth. They are all just atoms, one no more important than the other.

But what ultimately convinces him to return to Earth with Laurie is the “thermodynamic miracle” of her birth. The love between Sally Jupiter and Eddie Blake the man she had every reason to hate forever that led to the birth of Laurie.

Plot-wise, the revelation of Laurie’s true father provides a reason for two of the main characters to head back to Earth and return toward the story’s denouement. Character-wise, it provides Laurie with a missing piece of her life. Now she knows where her anger comes from, and what has been hidden from her all these years. She has been part of a conspiracy of ignorance all her life, and that changes her attitude toward the world, it would seem. If the world lasts long enough for her to do anything about it.

Issue #9 concludes with a monologue by Dr. Manhattan as he transports himself and Laurie back home, and in that speech, he reveals one of the major facets of Watchmen‘s theme: “We gaze continually at the world and it grows dull in our perceptions. Yet seen from another’s vantage point, as if new, it may still take the breath away.”

Comics, and the superhero genre, are not lifeless. They just need to be approached from a fresh perspective. So says Dr. Manhattan in 1987, and who can argue with a radioactive naked blue guy?

NEXT: Watchmen Part 4 Everything Goes Psychic Squid

Tim Callahan writes about comics for Tor.com, Comic Book Resources, and Back Issue magazine. Follow him on Twitter.